tl;dr: Chart creators often extend the quantitative scale in their charts to include zero when it’s not necessary, or don’t extend it to zero when it is necessary. Making the wrong design choice can make charts hard to read, distort readers’ perception of the data, or hide key insights. Expert opinions differ on when it is and isn’t necessary to extend a chart’s scale to zero, but most of the opinions that I’ve seen are, I think, too simplistic. Determining when zero is or isn’t necessary is surprisingly complex and multi-factorial (hence this 4,600-word article), but it can be captured as a decision tree of rules that chart designers of any experience level can follow to guide them to the right choice in any situation. Feel like coming down the rabbit hole with me to find out what are all of the factors that affect this decision?

The question of when it’s necessary to extend the quantitative scale in a chart to include zero and when it’s OK to “truncate” the scale (start it at something other than zero) has been bandied about for decades at least, and there’s plenty of disagreement and second-guessing among experts on this topic. Every so often, a research study comes along that seems to offer guidance, but, as soon as it’s published, people point out potential limitations or exceptions to the study that keep the waters nice and muddy.

Like many others, I have an opinion on this topic. Perhaps unlike many others, my opinion is, “The rules for determining when it is and isn’t necessary to include zero in a chart’s scale are surprisingly complicated.” As I see it, most—if not all—of the controversy around this topic arises from the fact that people have been arguing for or against rules that are too simplistic, i.e., that don’t account for all of the many factors that determine when it is or isn’t necessary to extend the scale to zero. What are those complicated rules? I’ll get to them in a moment, but, first, I think it would be useful to address...

Some simple rules that don’t work

Such as…

“Always extend the scale to include zero.”

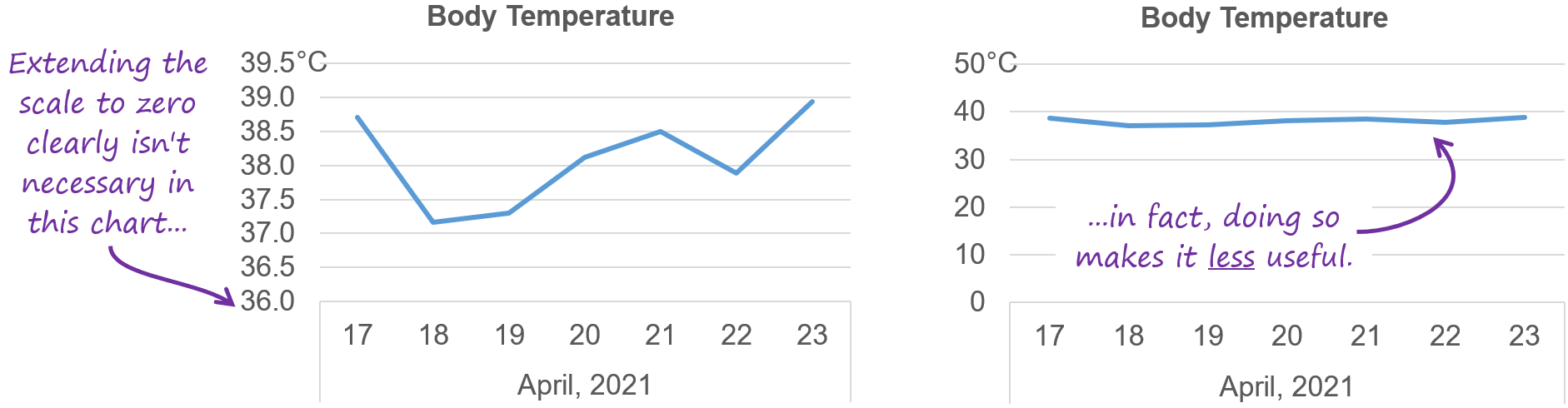

According to this rule, the chart on the left would be “wrong” and would need to be “corrected” to the version on the right:

I don’t know anyone who would think that the chart on the left is “wrong”, or that the “corrected” chart on the right is better. Clearly, then, it’s not always necessary to extend the scale to include zero.

OK, so how about…

“Extending the scale to include zero is always optional.”

According to this rule, the chart below on the left would be OK, even though it has a truncated scale:

With the chart on the left, if the reader isn’t paying attention, they’ll conclude that Canada is about twice as big as Brazil because its bar is about twice as long. As the version on the right (which starts the scale at zero) shows, however, that’s not even close to being true. Even if the reader is paying attention and does notice that the scale in the chart on the left doesn’t start at zero (and that’s a big “if”), what that truncated scale really says is “the lengths of these bars don’t accurately represent the quantities in this chart, so don’t compare these values based on bar lengths”. Uhh… thanks? Clearly, the truncated scale in the chart on the left is problematic, so the rule can’t be that zero is always optional, either.

So, extending the scale to include zero seems to be required in some situations, but optional in others. The obvious next question is, of course, in which situations is zero required, and in which can the scale be truncated? There are a few common answers to this question floating around, but I think that they’re still too simplistic, for example…

The bar chart rule

Many dataviz experts recommend that…

“It’s always necessary to extend the scale to include zero in bar-based charts (bar charts, stacked bar charts, clustered bar charts, etc.), but it’s always optional in other chart types.”

I agree that it’s always necessary to extend the scale to include zero in a bar chart; that’s pretty self-evident from the “Land Area by Country” bar chart example above, I think. I am, however, a lot less certain about making zero optional solely because a chart is a line chart, scatterplot, or any other non-bar-based chart type. Why? Well, have a look at this line chart:

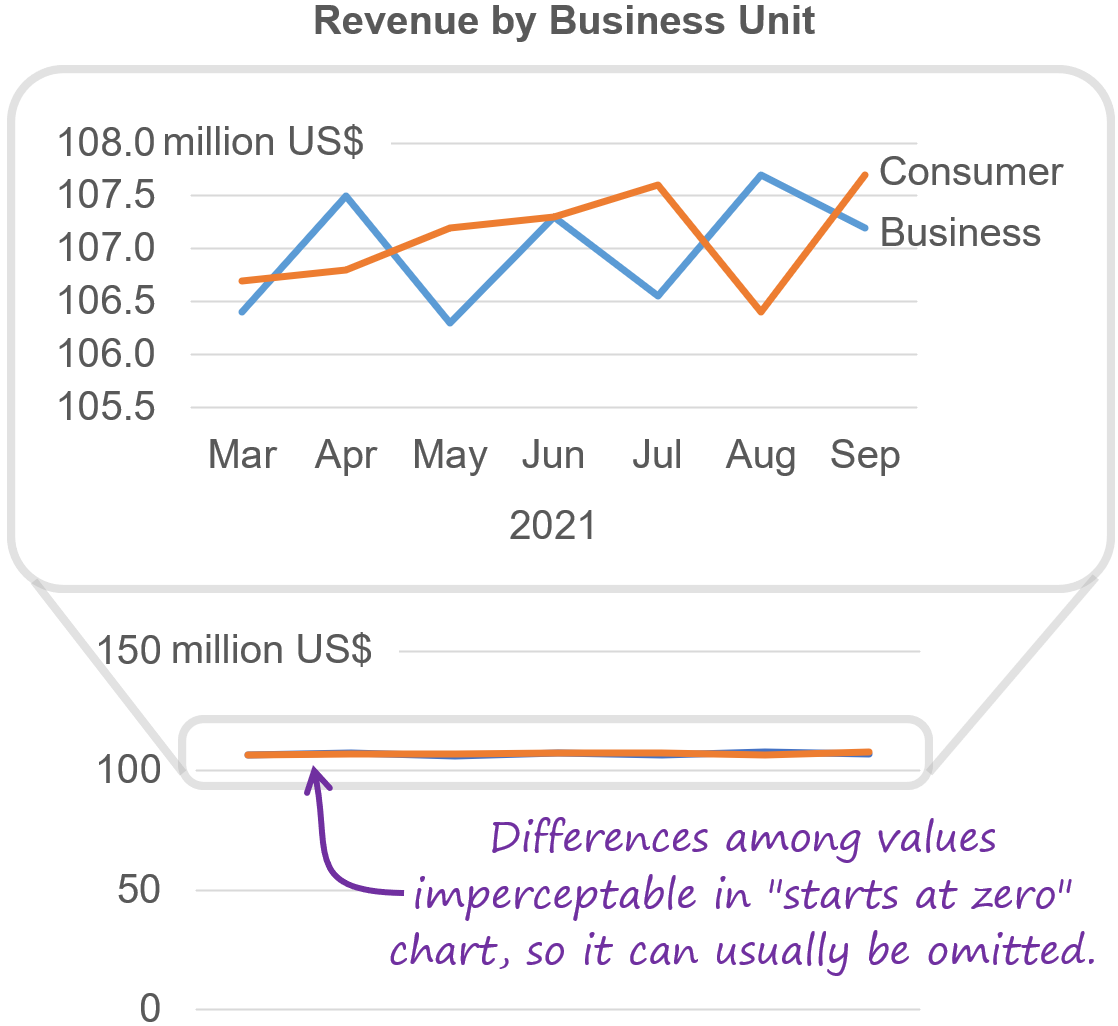

Many experts would say that it’s OK to truncate the scale in this chart because it’s not a bar chart. I wouldn’t feel comfortable publishing a chart like this, though. Why not? Well, it is true that readers won’t be thrown off by “wrong” bar lengths in a chart like this since there aren’t any lengths of bars to compare. There are, however, heights of points. This chart works by representing greater quantities (i.e., higher monthly revenues) as higher points on a line, and lower revenue as lower points. The problem, of course, is that a point such as August on the Business (blue) line is about three times higher up in the chart than the July point, so it would be natural to perceive the revenue for August as being three times higher than that of July. Most people who are likely to read this article will quickly realize that that’s not a correct reading of this chart, but I’ve seen enough people make this type of mistake in practice for it to worry me, and research suggests that this is a genuine concern.

Even when readers do interpret a chart like this correctly, though, it’s hard for them to get a sense of scale from it. The Business (blue) line looks like it’s quite volatile (bounces around a lot over time), but is it really? Was that dip in the Consumer (orange) line in August actually a big deal or not? In order to perceive basic insights like these, readers have to try to imagine what this chart would look like if the scale were extended to zero, i.e., they have to try to generate something like this in their head:

Generating a chart like this in one’s head requires a fair amount of cognitive effort, and most people won’t be able to do it very accurately. It’s only in this re-imagined version of the chart, though, that the reader can see that, for example, these measures really aren’t volatile at all, and that the August dip in the Consumer line probably isn’t a big deal—even though it looked dramatic in the original chart.

Those are the kinds of reasons why I wouldn’t feel comfortable publishing a chart like this with a truncated scale.

Of course, the version of this chart with the scale extended to zero has its own problems, too. Because all the values fall within a narrow range that’s far from zero, they all get crushed into a tiny region of the chart, making it difficult to see the small differences that do exist among them. Now, that’s not automatically a problem since, if the insight that we need to communicate about this data is that these values are all very similar to one another, or that they’re very stable over time, the “scale starts at zero” version of this chart communicates those insights perfectly as-is and so wouldn’t need to be “fixed”.

If, however, we need to say something about the small differences among the values or feature the small patterns of change that they are experiencing, the “starts at zero” version of this chart obviously wouldn’t cut it. But I’m not comfortable showing the “truncated scale” version of this chart, either, for the reasons that I mentioned earlier. What to do?

One solution that you might have seen before is to break the scale, like this:

This solution doesn’t address any of the concerns that we just saw, though. Perceptually, it’s essentially identical to the “truncated scale” version of this chart, and it has all the same problems (exaggerating small differences among values, making it hard for readers to get a sense of scale, forcing readers to imagine what the chart would look like with the scale extended to zero, etc.). Is there a better solution? I think so. We could use…

Inset charts

Inset charts such as the one above are safer than just showing a “truncated scale” chart and they make life a lot easier for readers since they’re not forced to imagine what the “scale extends to zero” version of the chart would look like in order to get a sense of scale, since that chart is included. Inset charts make small differences among values easy to see (if it’s necessary to show those small differences for the purposes of the chart) and they allow readers to see the “big picture” at the same time, to get a sense of scale without having to imagine charts in their head. This technique isn’t limited to line charts; it can be used with almost any chart type:

The main downside of inset charts is that they’re hard to automate, for example, on a dashboard of live, updating data. They can be very useful in “hand-crafted” presentations, reports, documents, etc., though.

So, is that the rule that we need to follow to determine if it’s OK to truncate the scale in a chart? Could we say that we should…

“Always extend the scale to include zero and, if all values fall within a narrow range that’s far from zero and it’s necessary to feature small differences among the values, add an inset chart with a truncated scale.”

I think we’re making progress with this rule and it’s already more robust than most other rules that I’ve seen, but there are a few important exceptions, specifically…

If the data falls within a range that’s so narrow that the differences among the values are imperceptibly small in an “extends to zero” chart. In these situations, the “extends to zero” chart doesn’t add much because it’s effectively just showing a single value, i.e., the distance from zero to the tiny range of values in the chart. If you’re certain that the audience is sophisticated enough to quickly realize that the differences between the values would be imperceptibly small in an “extends to zero” chart, it could be omitted:

If the distance between the values and zero is truly, completely irrelevant to the purpose of the chart. While this is rare, it does happen. For example, if the sole purpose of a “Daily Revenue” chart is to show which days were above a daily revenue target and which days were below, it’s technically not necessary to show the “scale extends to zero” version of the chart to communicate that particular insight. Be careful in these situations, though, since the audience might try to make other types of inferences based on the chart that may be perceived incorrectly if only a chart with a truncated scale is shown, with no “extends to zero” version along with it (e.g., how volatile “Daily Revenue” is). If you’re even a little uncertain about this, I’d use an inset chart in these situations to be on the safe side, but, technically, this is an exception.

When the audience is very familiar with the particular data in a chart, and they’ve already developed an intuitive sense of scale for that data over time. For example, if the workers in a manufacturing facility look at a “Units Manufactured per Hour” chart all the time, they may develop a strong intuitive sense of the typical range and scale for that data. Once that sense of scale becomes intuitive, it becomes optional to show the “extends to zero” chart since that chart is “already in the audience’s head” and so requires almost no effort to imagine what it would look like.

If we’re in one of these exceptional cases and we end up showing only a chart with a truncated scale, we can run into the “bar chart issue” that we saw before, though. For example, in the bar chart below, it does look like Plant B has about “twice the quantity of Units per Hour” as Plant C because its bar is twice as long, but, as we saw previously, that’s not even close to true:

To mitigate this issue, if we’re only showing a chart with a truncated scale with no accompanying “starts at zero” version, we can avoid using chart types that represent values as lengths or widths of shapes, such as bar charts and stacked area charts. Instead, we can use chart types based on 2D position (line charts, dot plots, etc.), color (heat maps, etc.) or other “non-length/width” attributes. This doesn’t completely mitigate the “proportional comparison” issue, but it helps:

When showing a chart with a truncated scale, it’s a good idea to widen the scale so that it’s a little wider than the range of the data in the chart, i.e., so that there’s a bit of “padding” (whitespace) around the values. This makes the chart look less crowded and makes it clear that the chart is showing all the values, i.e., that none of them have been “cut off” by the edge of the chart area:

Occasionally, it can make sense to make a truncated scale even wider, specifically, when the data has an expected or typical range. For example, if the “Units per Hour” values typically range between 8,300 to 8,700, we should make our truncated scale span that range to communicate that the current values in the chart are, for example, in the lower end of their typical or expected range:

We’d better update our rule to reflect all these new considerations, then:

“Extend the scale to zero and, if all values fall within a narrow range that’s far from zero AND it’s necessary to feature small differences among the values, add an inset chart with a truncated scale, except if any of the following are true, in which case just a chart with a truncated scale can be shown:

All values fall within a range that’s so narrow that the differences among them are imperceptibly small when the scale is extended to include zero.

The distance from zero to the values is completely irrelevant to the purpose of the chart and there’s no concern that the audience will make unintended inferences.

The target audience is very familiar with the data and already has an intuitive sense of the scale of that data.

When showing a chart with a truncated scale and no accompanying ”starts at zero” chart:

Avoid chart types that are based on the lengths or widths of shapes.

Add padding to truncated scales so that the values aren’t too close to the edge of the chart area and, if the data has a typical or expected range, widen the scale to span that range.”

Our rule is getting complicated now, though, so it might be clearer to represent it as a decision tree instead of prose:

A little easier to follow now, I think. We’re getting closer to a set of rules that will work reliably in all situations, but we’re not there yet. We also need to consider if the scale in our chart is a…

“Ratio” or “non-ratio” scale

Have a look at this chart of our organization’s average client satisfaction ratings for the last five months:

If we apply our latest rule, we get this:

The “extends to zero” chart doesn’t really feel necessary here, though, does it? In fact, just showing the “truncated scale” chart seems to work just fine on its own in this case. Why? Well, this is where things start to get a little more complicated (I warned you… right in the title…)

Even though the “Client Satisfaction Rating” scale in this chart looks the same as scales in other charts that we’ve seen so far, it’s fundamentally different in two ways:

In the scales in other charts that we’ve seen, zero represents an absence of quantity. For example, on a scale of “Revenue ($)”, $0 represents the absence of a quantity of revenue. On a “Client Satisfaction Rating” scale such as the one in the chart above, however, “0/10” doesn’t represent “the absence of a quantity of satisfaction”, it represents a very low level of satisfaction (or, more likely, a very high level of dissatisfaction), which isn’t the same thing as “the absence of a quantity of satisfaction”. In fact, “the absence of a quantity of satisfaction” doesn’t even really make sense as a concept.

On the scales in other charts that we’ve seen so far, we can make proportional comparisons. For example, on a scale of “Revenue ($)”, we can say that $300,000 is three times as much as $100,000. On a “Client Satisfaction Rating” scale, however, does it make sense to say that a rating of 9/10 is “three times as much satisfaction” as a rating of 3/10? Statements like that are nonsensical when you think about them for a moment…

Scales on which zero represents an absence of quantity and that allow proportional comparisons are called ratio scales, and include scales like “Revenue ($)”, “Headcount (Employees)”, and “Vehicles per Hour”. (I should note that most definitions of “ratio scale” specify that they can’t include negative numbers, but, for the purposes of deciding whether zero is or isn’t required, ratio scales include scales like “Profit ($)”, which can be both positive and negative.)

Examples of scales on which zero doesn’t represent an absence of quantity and on which proportional comparisons don’t make sense would be “Client Satisfaction Rating”, “Movie Rating”, “Sales Performance Rank”, and “IQ Score”. These “non-ratio” scales have several different names but those don’t matter for the purposes of this article so I’m just going to stick with calling them “non-ratio scales”.

On non-ratio scales, zero isn’t “really zero”, so we can actually use any numerical scale we like, and whether the scale that we choose includes zero or not doesn’t matter. For example, we could rate movies on a scale of 70 to 75 stars if we really wanted to, or -10 stars to +10 stars, as long as our readers understood that a “70-star movie” or a “-10-star movie” meant that it was terrible. Therefore, if the scale in our chart is a non-ratio scale, it doesn’t matter if it includes zero or not. The only thing that matters is that readers are able to associate different numbers on the scale with different levels, as in “a high level of cinematic quality”, or “a low level of academic performance”. We’d better add this to our decision tree, then:

Note that non-ratio scales don’t really represent “quantities” in the way that most people think of that concept, which is why phrases like “a large quantity of cinematic quality” or “a small quantity of sales performance rank” sound weird. It’s debatable, then, whether we should even be showing non-ratio values in a graph that has what looks like a quantitative scale, since this could encourage readers to make proportional comparisons of non-ratio numbers which, as we just saw, don’t make sense.

There are two design best practices that we can use to discourage readers from making proportional comparisons in charts with non-ratio scales:

Avoid using chart types that represent values as lengths or widths of shapes, such as bar charts and stacked area charts. Instead, use chart types based on 2D position (line charts, dot plots, etc.), color (heat maps, etc.) or other “non-length/width” attributes charts, i.e., similar to the best practice that we saw earlier for truncated ratio scales. This doesn’t completely mitigate the issue, but it helps:

2. Label the levels that are associated with different number ranges:

This encourages readers to focus more on the levels in which non-ratio numbers fall (which they should do), and less on how those numbers compare proportionally with one another (which they shouldn’t do).

In situations when the values in our non-ratio chart have an expected or typical range, widen the scale to span that range for reasons similar to those that we saw when discussing truncated ratio scales earlier:

We should probably add these best practices to our decision tree as well, then:

Now that we understand the differences between ratio and non-ratio scales and how they affect whether or not we can truncate the scale in our charts…

We need to talk about temperature.

In debates about when it’s necessary or optional to extend a chart’s scale to include zero, charts of temperature often come up as examples of when it’s clearly not necessary to extend the scale to zero. Temperature has some unique subtleties, though, so let’s have a closer look at it in the context of the rule set that we’ve developed so far. Have a look at this chart of temperature values:

I agree that this chart is fine because the “temperature in °C” scale is a non-ratio scale:

Zero isn’t actually zero, i.e., 0°C doesn’t indicate the complete absence of heat energy in the air.

Proportional comparisons don’t make sense, e.g., 10°C isn’t “twice as hot” as 5°C.

Because the scale in this temperature chart is a non-ratio scale, it doesn’t matter if zero is included in the chart’s scale or not. The only thing that matters in a chart like this is that readers are able to associate different numbers (e.g., 22°C, 0°C, -14°C, etc.) with different levels (in this case, levels of comfort), and they can do that just fine based on the scale in this chart. Same goes for the Fahrenheit scale, assuming the audience is able to associate different numbers on that scale with different levels of comfort.

Now, temperature is different than other non-ratio scales like, say, a movie rating scale, because temperature values are empirical measurements, whereas movie ratings are subjective assessments (by critics, audience voting, etc.). For the purposes of determining if we can truncate the scale or not, though, that distinction doesn’t matter. If zero isn’t really zero and proportional comparisons don’t make sense, then the scale is a non-ratio scale and should be considered as such for the purposes of determining whether it is or isn’t necessary to extend the scale to zero—regardless of whether the values on the scale are subjective assessments or empirical measurements.

Many people who are likely to read this article probably know that there’s another temperature scale called the “Kelvin scale”, that’s used primarily by scientists. On the Kelvin temperature scale, zero does represent a complete absence of heat energy (a.k.a. “absolute zero”, or -273.2°C) and 100 Kelvin does represent twice as much heat energy as 50 Kelvin. If a chart shows temperature in Kelvin, then, the scale in that chart would be a ratio scale, not a non-ratio scale, and the rules for charts with ratio scales would apply when determining whether the scale needs to be extended to zero or not (i.e., extend the scale to include zero unless the values all fall within a very narrow range, add an inset chart if necessary, etc.).

So, temperature is a tricky case because it can be either a ratio scale or a non-ratio scale, depending on the scale’s unit of measurement. I’m not aware of any other measures for which this is the case, but there are probably a few others floating around out there. For the vast majority of measures, though, they’re either always ratio scales or always non-ratio scales, regardless of unit of measure. So, yes, temperature is a tricky case, but our latest rule/decision tree handles it properly and so doesn’t need to be updated.

We’re getting there, I promise, but we also need to talk about…

Situations in which the scale almost includes zero

Have a look at this chart:

Now, if you’re like me, you find that the scale in this client satisfaction chart looks a bit “wrong” because it ends just before zero, but doesn’t actually include zero. We tend to assume that scales that end close to zero actually end at zero, and are a bit thrown off when they don’t. Even though “Client Satisfaction Rating” is a non-ratio scale (so we technically don’t have to include zero in the scale), we should probably still extend the scale to zero because the scale ends so close to zero.

The rule of thumb that I use in situations like these is that, if zero is within about the distance from the lowest value in the chart to the highest value (a.k.a., the “spread” of the values), I’ll extend the scale to include zero, even if it’s technically not necessary to do so. For example, in the chart above, the spread of the values is the distance between 7.7 (the highest value) and 3.2 (the lowest value), which gives us a spread of 4.5. Zero is within 4.5 of 3.2 (the value that’s nearest to zero), so we should extend the scale to include zero:

Obviously, if our scale doesn’t have a zero (e.g., a scale of movie ratings that ranges from one to five stars), then this best practice wouldn’t apply.

We should add this to our decision tree as well, then:

“So is THAT it? Holy crap, I hope that’s it.”

Yes, that’s it. I think that this final decision tree takes all relevant considerations into account and allows chart creators of any experience level to reliably determine whether extending the scale to include zero is required or optional in any situation.

As an added bonus, these rules also answer the age-old question of when color scales should start at zero or the lowest value in the data set:

“These rules are too complicated!”

I completely agree. As it turns out, though, determining when it’s necessary or optional to include zero in a chart’s scale is an inherently complicated, multi-factored decision. I wish these rules were simpler but, whenever I try to simplify them, I break something, i.e., I can imagine scenarios in which following the rules would lead to a bad design choice. If you can see a way to simplify them, though, please do pipe up in the comments…

When all the factors that affect this decision are spelled out like this, it becomes a lot less surprising that people have been arguing about it for decades (or, probably, much longer). Few people seem to realize just how complicated and multi-factored this decision actually is, and most argue for or against rules that, as I mentioned at the beginning of the article, are too simplistic. I dare to hope that this article (or some future revision of it) will finally resolve those arguments, if anyone actually reads the whole thing 😊.

BTW, this decision tree will be added to my Practical Charts course, which features over twenty other tools that allow chart creators of any experience level to make the best choice for many other common but tricky dataviz design decisions. Because this is the first wide exposure that this particular tool is receiving, I fully expect that people will think of scenarios that I haven’t considered, and in which the decision tree wouldn’t recommend what they consider to be the best design choice. If you can think of any such scenarios, please (please!) pipe up in the comments so that I can tweak the decision tree to account for them.

A huge thanks to Xan Gregg for his valuable comments and suggestions on a draft of this article. If you’re not already following Xan on Twitter, you really, really should.

By the way...

If you’re interested in attending my Practical Charts or Practical Dashboards course, here’s a list of my upcoming open-registration workshops.